Introduction & Stakes: Armenia’s Civic Paradox and the Road to 2026

In April 2018, a popular movement led by journalist, former political prisoner, and MP Nikol Pashinyan peacefully overthrew the semi-authoritarian regime of President Serzh Sargsyan (the so-called “Velvet Revolution”), demonstrating that a nonviolent transition to democracy was indeed possible.[1] Since then, Armenia has exemplified a paradox in democratic evolution: it boasts one of the most open civic and media environments in the post-Soviet space, yet simultaneously faces mounting threats to civil liberties, political pluralism, and civic resilience. The Velvet Revolution ignited unprecedented civic energy, toppling entrenched elites and ushering in democratic hopes.[2] But the ensuing years have tested the fragility of these gains.

The trajectory of Armenian civil society mirrors both progress and precarity. Key reforms included removing NGO reporting burdens, launching transparent grant systems,[3] and legally recognizing volunteering.[4] At the same time, civic actors have faced smear campaigns, legal harassment, surveillance laws, and a rising wave of populist and nationalist rhetoric.[5][6] This contradictory reality defines Armenia’s civic space as “narrowed”[7], yet not closed, repressed, or obstructed like neighbouring Azerbaijan, Iran, Turkey, and Georgia.

Civil society in Armenia emerged over decades, shaped by post-Soviet transformations, donor influxes, and protest legacies.[8][9] The roots of civic engagement can be traced to grassroots movements and informal activism during the late Soviet period. These evolved into more formalized structures in the 1990s and 2000s, although they remained constrained by authoritarian governance. The 2018 revolution catalysed this latent capacity, as NGOs and civic movements were able to quickly mobilize and channel popular demands into reform agendas. Yet the independence of civil society organisations (CSOs) remains uneven. Some CSOs, particularly in Yerevan, maintain watchdog roles; others have become aligned with political movements.[10] This urban-rural divide is stark: in Yerevan, well-established CSOs influence policy, but in rural regions many activists struggle against funding shortfalls and local skepticism.

Looking ahead, the upcoming June 2026 parliamentary elections represent a critical juncture. They will serve as a referendum not just on governance, but on the integrity of Armenia’s democratic space. Will the country reaffirm its commitment to pluralism, accountability, and civic participation, or succumb to global and regional trends of shrinking space? The stakes are high for Armenia’s young democracy on the road to 2026.

Populism and Ruling Party Dynamics

The post‑2018 era in Armenia marked a moment of optimism: the Civil Contract Party under Nikol Pashinyan rode the wave of the Velvet Revolution into power, promising openness, transparency, and a break with Armenia’s post‑Soviet patrimonial legacy. Yet as the initial reform momentum slowed, the party increasingly displayed traits characteristic of populist incumbents seeking to consolidate power: adversarial media relations, boundary‑shifting rhetoric, and the invocation of national‑sovereign tropes to defend majoritarian rule.[11]

One frequently used government strategy has been to target the media and opposition voices. Investigative journalists who exposed defence procurement controversies, or flagged nepotism and opaque public contracts, have been accused of undermining national solidarity, branded “unpatriotic” and treated as part of a politicised “fifth column”. In the second quarter of 2024 alone, 15 cases of physical violence against journalists (most of which were the result of disproportionate actions of the law enforcement bodies), 24 injured, 71 other pressures[12], 122 violations of the right to receive/disseminate information were reported.[13]

Female journalists face a double burden of harassment and misogynistic abuse, specifically in online media, with cases of victim blaming, gender stereotyping, and framing by opposition that female politician’s legislative proposals are part of the agenda of Soros.[14] By personalising and gendering criticism, the ruling and opposition elite shifts the focus from institutional reform to individual reputational warfare. This aligns with the designation of gendered attacks as a parallel axis of civic shrinkage.

At the rhetorical level, nationalism has been weaponised. Aggressive activities and campaigns by (opposition) nationalistic organizations against civil society, specifically those working in the fields of human rights and protection of minorities, have further impacted the already shrinking civic space in the country.[15] This has been paired with a lack of adequate response from governmental bodies, such as the prime minister and judicial institutions.

These patterns echo global populist tendencies: the blurring of opposition/civil society boundaries; the personalisation of political attacks; the nationalist framing of critique; and the strategic use of media hostility. In Armenia’s case, the challenge is compounded by its geostrategic location, recent conflict trauma, and the still‑fragile institutional architecture of its democracy. The cumulative effect: those identified as dissident actors by the state are not only delegitimised in public, but are also increasingly constrained in practice, which has resulted in the further shrinking of civic space whilst maintaining a thin veneer of democratic pluralism.

Protest, Policing & Legal Constraints

In the years following 2020, the protest landscape in Armenia has grown more contested, followed by a more aggressive approach by the state. Whereas the 2018 revolution emphasised non‑violent mass mobilisation, subsequent protests, triggered by border demarcation issues with Azerbaijan, social‑economic grievances, or environmental concerns, have often been met with a disproportionate response by the national security apparatus.[16]

According to the Aram Manoukian Institute’s 2025 white‑paper, protest policing since 2023 has undergone a qualitative shift which has resulted in the routine deployment of elite tactical units, use of stun grenades and tear‑gas in otherwise peaceful settings, and absence of adequate advance warnings or medical safeguards.[17] Amnesty International likewise reports Armenian police used “unlawful force” during the April‑May 2024 protests, requiring the Prime Minister to resign. Furthermore, in June 2024 clashes broke out during protests against the border demarcation deal with neighbouring Azerbaijan leaving over 100 injured and more than 90 detained.[18] Moreover, several opposition politicians and civic activists were detained during protests linked to the ongoing border-demarcation negotiations with Azerbaijan. Among those arrested were prominent critics of Prime Minister Pashinyan, who had appeared on independent media platforms. CSO Meter noted that a June 12 2024 assembly resulted in injuries to more than 100 participants and media workers after stun grenades were deployed.[19]

Recent events illustrate how policing and legal repression are becoming centralised instruments of political control. In October 2025, riot police violently arrested Gyumri’s mayor, a member of the opposition party, Vartan Ghukasian, and more than forty of his supporters amid clashes at the municipal building. The Anti-Corruption Committee’s charges were widely perceived as politically motivated, particularly after Prime Minister Pashinyan’s earlier pledge to oust the mayor. Multiple municipal employees were later detained, including relatives of Civil Contract party members, underscoring the blurred line between legal enforcement and political retribution. [20]

Similarly, in Vagharshapat, the fourth largest city in the country and the centre of the Armenian Apostolic Church, observers documented electoral misconduct during the November 2024 municipal elections. The Corruption Prevention Commission’s failure to publish mandatory financial disclosures, alleged vote-buying by Civil Contract candidates, and the misuse of administrative resources demonstrates misuse of power by an allegedly independent body.[21]

Recent legal measures serve to further exemplify the increasingly authoritarian direction in which the government is moving. In 2024 draft defamation/disinformation bills proposed criminal penalties for harsh speech against public officials. Parallel to this, strategic lawsuits against public participation (SLAPPs) are emerging, with minimal oversight of their abuse, dominantly filed by entities and individuals with large political and economic resources against media, individual journalists and human rights defenders (70% of the total lawsuits).[22] In addition, recent amendments to Armenia’s Law on Police empower the Ministry of Internal Affairs with real-time biometric surveillance and facial recognition across public spaces, measures that CSOs warn may be used to monitor, intimidate, or suppress protestors and civic actors.[23]

In spite of this, the authorities claim that enhanced video surveillance and biometric monitoring are needed to “strengthen the security of public spaces” and combat crime or terrorism[24] . Similarly, hardline protest policing is framed as preventing instability or foreign-provoked unrest in a volatile post-war context. Government representatives also reject the term “SLAPP,” insisting that lawsuits against media or activists are legitimate efforts to protect officials’ reputations and counter disinformation.

That said, it would be hard to deny that civic space in Armenia is not shrinking, and an increasing body of evidence supports this: civil society actors report frequent censorship, difficulty mobilising outside urban hubs, and reluctance to lead large‑scale visible protests given the risks of surveillance or police escalation. Government officials defend their actions as necessary for the preservation of law and order, but to many, the Armenian government’s aggressive policing and surveillance appears plainly antidemocratic.

Minority Rights and Institutional Safeguards

Despite formal commitments to human rights and equality, Armenia continues to lag in protecting and integrating its most vulnerable populations. A key gap is the absence of a comprehensive anti‑discrimination law that is inclusive (provisions for sexual orientation and gender identity).[25] Hate speech remains prevalent, particularly online but also within political discourse. As the constitutionally recognized national church, the Apostolic Church wields considerable moral authority. Its leadership has historically espoused conservative stances, for instance, unequivocally rejecting LGBTQ+ relationships, thereby reinforcing traditional attitudes in society.[26] While the Church does not directly dictate policy, its pronouncements contribute to a climate in which progressive reforms on gender or minority rights are cast as attacks on Armenian identity.

Institutional safeguards for rights exist, but they are under strain. The national human rights institution, the Human Rights Defender’s Office of Armenia (HRDO), is formally independent, yet has seen its credibility wax and wane. While the HRDO continues to represent a key institutional safeguard within Armenia’s human rights architecture, public confidence in the institution has fluctuated sharply over time[27]. Public confidence spiked to an all-time high of 81% in 2021 amid the post-war crisis, reflecting citizens’ urgent hopes for accountability. But by 2024, trust in the HRDO plummeted to 33%, with 42% expressing distrust. This dramatic reversal suggests a crisis of confidence in whether the ombuds institution remains truly neutral. The sharp swings in trust could also point to the politicization of the office in the public eye.

Civil Society Infrastructure & Funding

An oft-overlooked dimension of Armenia’s civic space is the infrastructure that sustains civil society, funding, public trust, and organizational capacity. Many Armenian CSOs operate in a perpetual scramble for resources. According to the USAID CSO sustainability index, financial liability has long been the weakest dimension, with uneven distribution of public funding in favour of CSOs providing services in Armenia, at the cost of those with watchdog functions, human rights advocacy, or environmental focus.[28] With fewer long-term grants and a shift toward short-term, crisis-response projects, many organizations operate hand-to-mouth. Additionally, the closing down of USAID operations in January 2025 dealt a major blow to Armenia’s civic and media ecosystem: the freezing of U.S. assistance has forced many grassroots organizations to shut down, compelled larger CSOs to scale back, and cut off funding for independent outlets, significantly weakening pluralistic oversight and public accountability.[29] Combined with regional instability and domestic political polarisation, these factors are shrinking the operational space for CSOs across Armenia.[30]

One potential counterweight is the Armenian diaspora, which is one of the largest per capita in the world. The diaspora has historically played a philanthropic role in Armenia, funding humanitarian projects, schools, and churches. Increasingly, diaspora donors and organizations are stepping in to assist civil society as well. For example, diaspora-led charities and foundations have supported independent media outlets, human rights initiatives, and disaster relief efforts. Analysts point to the diaspora’s tradition of charitable giving as a resource that could partially fill the gap left by departing international donors.[31] However, while the diaspora is a vital source of goodwill and funds, it cannot single-handedly replace institutional donors.

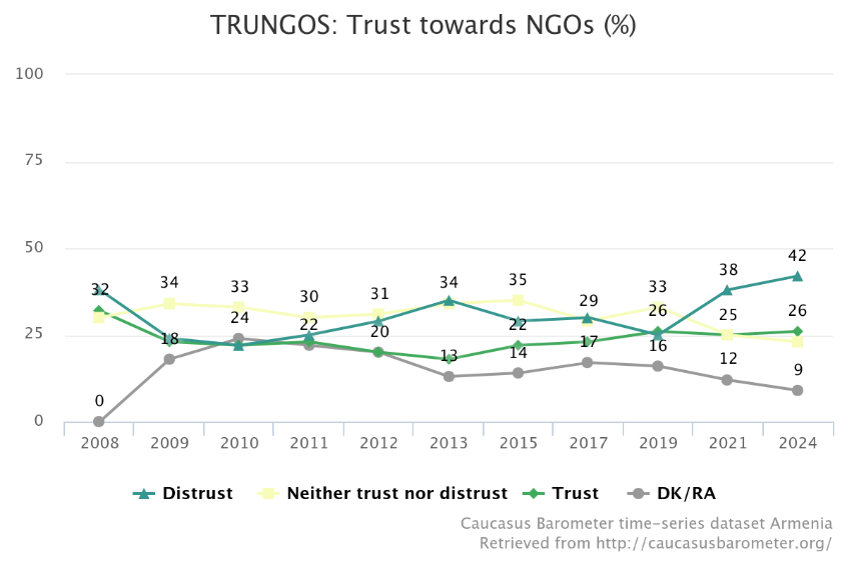

Public trust is the other critical pillar of civil society infrastructure, and here Armenia faces a troubling trend. Trust in NGOs and media has been declining, undermining the legitimacy of the civic sector. According to the Caucasus Barometer, conducted by CRRC-Armenia since 2008, public trust in NGOs has had an average of 23.6%.[32] Alarmingly, distrust toward NGOs rose to an all-time high of 42% in 2024. The media fares no better: while distrust averaged 31.7% between 2008 and 2019, it surged to 69% in 2021, and although it declined slightly by 2024, distrust remains high at 49%.[33] These trends suggest not only increasing scepticism toward key democratic actors, but a broader crisis of civic legitimacy.

Economic hardship further dampens civic engagement. Since independence from the Soviet Union, Armenia’s population has faced inflation, unemployment, and the aftershocks of war, leaving many people focused on day-to-day survival rather than activism. When households are worried about jobs and prices, volunteering or attending public hearings is a luxury few can afford. This economic strain, combined with cynicism about institutions, yields low participation rates in elections, with voter turnout in recent elections around 49%.[34] Local elections in Yerevan in 2023 recorded the lowest turnout in history: only 28%[35] of the eligible population voted, further weakening democratic resilience. The erosion of trust may also contribute to political disengagement, reflected in low motivation to participate in upcoming elections[36] or civic initiatives.

Comparative Lens: Georgia, Serbia, and Moldova

Armenia’s trajectory becomes clearer when viewed against regional peers experiencing similar democratic pressures. Georgia, once a democratic success story, enacted a “foreign agents” law in 2024 that undermines NGOs and stokes public hostility.[37] This marked a decisive turn away from EU-aligned reforms and toward an authoritarian model of civic control. The Georgian case illustrates how quickly a reformist government can backslide: using legal tools and propaganda, even a relatively open society can be pushed toward authoritarian practices in a short time. For Armenia, which shares a society-wide pro-democracy sentiment but also nationalist currents, Georgia is a cautionary tale of how democratic gains can be eroded if populist narratives go unchecked.

Serbia’s authoritarian slide has been marked by media repression, anti-protester violence, and smear campaigns against CSOs.[38] What distinguishes Serbia is the state’s use of hybrid tactics, formal legality cloaking informal coercion. Protesters face police brutality, while NGOs endure reputational attacks and intrusive audits. Serbia’s drift has occurred despite EU accession talks, showing that international engagement alone does not safeguard democracy.

In contrast, Moldova shows how political will and EU integration incentives can expand civic space through reforms and structured dialogue.[39] Since 2019, Moldovan civil society has benefited from state-CSO partnerships, tax incentives, and public consultation mechanisms. The recent elections in September 2025 resulted in a majority of the seats for the ruling pro-European party. Although progress remains fragile, and oligarchic interests and Russian influence still remain, Moldova underscores the potential for democratic resilience. For Armenia, Moldova is a reminder that political will and external incentives (like EU integration prospects) can significantly expand civic space.

These comparisons reveal that external engagement (such as EU incentives) and internal political will must operate in tandem to protect civic freedoms. Georgia’s regression underlines the vulnerability of even reformist states to authoritarian backlash when civic actors are framed as adversaries. Serbia warns of what happens when populist rhetoric goes unchecked by institutions. Moldova offers a model for embedding civic engagement into governance structures and reaping the benefits of cooperative pluralism.

Armenia’s divergence from Georgia and Serbia is instructive: it has avoided formal repressive laws but echoes similar nationalist rhetoric. Its alignment with Moldova, both rated highest on the 2024 CSO Meter, suggests a fragile potential for democratic consolidation, if reforms deepen and populist pressures are contained. Armenia therefore stands at a crossroads in the lead up to parliamentary elections in 2026 – it can opt to slide further into authoritarianism, as Georgia and Serbia have done, or it can choose to follow the Moldovan example and strengthen its democratic institutions and civil society.

2026 Election Risks and Scenarios

The parliamentary elections scheduled for June 2026 will be a pivotal stress test for Armenia’s civic space. Politically, the landscape heading into these elections is marked by weak and fragmented opposition and a disillusioned electorate. Pashinyan’s Civil Contract party dominates the scene, not because of overwhelming popularity (the Prime Minister’s ratings have dipped amid difficult peace negotiations), but because alternative contenders are scarce. The main opposition factions in parliament are led by figures from the old regime, ex-presidents and their allies, who many voters distrust. Newer political parties exist, but none have built a broad base or unified into a credible coalition. As one analyst observed, “opposition forces are either anti-democratic, fragmented, or unpopular”.[40]

Security incidents with Azerbaijan could justify emergency laws or suppress criticism. These patterns mirror 2020 and 2022 crackdowns. If public trust in electoral institutions erodes, post-election unrest is possible. Armenia’s prior experiences with disputed elections and mass mobilizations suggest the volatility of such periods. Yet resilience also remains possible. Civil-society coalitions have indeed emerged in Armenia, for example the Anti‑Corruption Coalition of Civil Society Organizations of Armenia, which coordinates public monitoring of anti-corruption reforms.[41] The 2024 Caucasus Barometer survey by the CRRC-Armenia found that despite widespread alienation from formal political parties, 74% of respondents believe Armenians have the right to freely express opinions and a similar share consider Armenia a democracy, albeit with “serious challenges”.[42][43] Meanwhile, the Organisation for Economic Co‑operation and Development (OECD) 2024 review indicated that over 66 % of public servants in Armenia report their organisations “collaborate effectively with stakeholders outside the public sector (e.g., academia, civil society organisations, media)”.[44]

Various scenarios could unfold. In one outcome, the elections are free, competitive, and peaceful. Civil society’s role in monitoring and civic education is respected, setting a precedent for institutional strengthening. In a medium-risk scenario, the elections occur without major fraud but are marred by inflammatory rhetoric and minor procedural irregularities. The government tolerates criticism but continues populist attacks on media and NGOs. In a worst-case scenario, civic freedoms are restricted under emergency decrees, opposition protests are violently dispersed, and independent observers are denied access. Such an outcome would likely trigger international condemnation and stall any progress toward deeper European integration.

Yet the 2026 elections carry strategic significance far beyond routine politics. They will likely determine the course of Armenia’s most critical national issues, notably the prospective peace agreement with Azerbaijan and potential constitutional changes. In fact, at a party congress in September 2025, Pashinyan declared that if Civil Contract wins in 2026, they intend to “establish the Fourth Republic of Armenia” by adopting a new constitution via referendum.[45] This proposal is not merely domestic posturing; it aligns with a key Azerbaijani demand that Armenia amend its constitution to renounce any territorial. In short, the 2026 elections are not just about who wins power in Yerevan, they are about whether Armenia’s experiment in democracy survives.

Conclusion: Between Fragility and Resilience

From the hopeful surge of Armenia’s 2018 Velvet Revolution to the ongoing challenges of war, polarization, and institutional strain, the civic space journey has been anything but linear. Yet, even under duress, Armenia has managed to preserve a degree of pluralism and civil engagement that distinguishes it in the region. The 2026 elections could either consolidate this fragile openness or reverse it dramatically. The evidence suggests a hybrid contraction: in many respects the space has narrowed; critical journalists face attacks, protesters face intimidation, NGOs are beleaguered, but it is not fully closed or systematically crushed as in outright autocracies. Instead, Armenia teeters between fragility and resilience. It remains a democracy on paper and in the hearts of many citizens, but the quality of that democracy hangs in the balance.

Armenia’s civic space stands at a crossroads. The forces of populism, nationalism, and securitization threaten to narrow participation and silence dissent. If these forces prevail unchecked, Armenia could gradually slide toward the kind of managed democracy or soft authoritarianism seen in some of its neighbors. Yet, equally present in Armenia are countervailing forces of democratic resilience. A vibrant core of civil society activists, human rights defenders, independent journalists, and engaged citizens continues to push back against illiberal currents. Public demand for fairness and accountable government, while muted by disappointment, still exists, seen in opinion surveys where a majority insist that Armenia should remain a democracy, albeit one with “serious challenges.” International support and attention also remain factors; Western democracies and organizations have not abandoned Armenia, and continued engagement provides both resources and moral support for keeping civic space open.

The next months are pivotal. Reforms introduced now could shape the rules of engagement for a generation. Reforms and proactive measures, such as safeguarding media independence, ensuring an even playing field in the elections, and protecting minority rights, could solidify the rules of the game and institutionalize democratic norms for a generation. Failure to act could see Armenia slide toward the kinds of systemic repression seen in Georgia and Serbia. The task before policymakers, media, activists, donors, diaspora, and citizens is clear: to turn fragility into resilience, and democratic aspiration into institutional reality. If Armenia can preserve and strengthen that space under duress, it will send a powerful message in a world where democracy is under siege.